I’d Like To Teach The World To Be More Socially Aware (But Should I?)

By

2 years ago

The power of storytelling in the modern age

In a world of social flux and the need for dramatic societal change, can brand advertising and marketing campaigns take on the role of moral arbiter? Yes and no, says Rory Sutherland.

Buy a copy of Great British Brands 2022 here

I’d Like To Teach The World To Be More Socially Aware (But Should I?)

In my childhood it was a long-standing joke that there were no famous Belgians. There’s a reason for this. It’s not that there are very few famous Belgians, but that once you’re Belgian and become famous, people who aren’t Belgian assume you’re French.

Canadians often complain about the same thing: whenever Canada produces a world-famous figure, unless they are an ice-hockey player or a maple syrup manufacturer, everybody assumes they’re American.

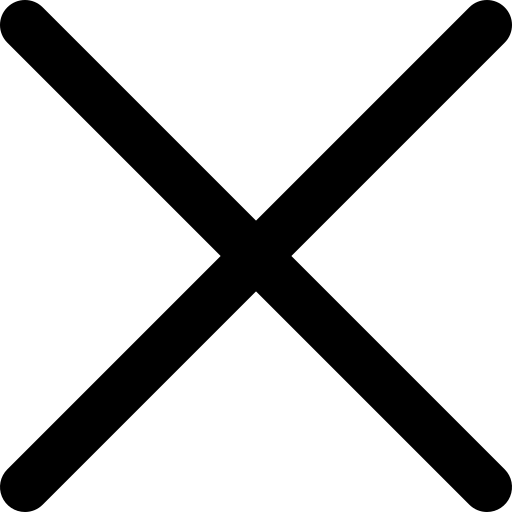

Steve Jobs was a brilliant designer but also a brilliant marketeer (Photo: Shutterstock)

I’ve spent 33 years of my life working in marketing and advertising. And one sad realisation this has brought is that marketing itself sometimes suffers from the Belgian problem. The reason is that if you do marketing really well, the credit generally goes somewhere else. Nobody (outside marketing) ever says, ‘Steve Jobs, what a marketing genius – what salesmanship!’ Instead they say, ‘What a brilliant inventor or designer!’ or, ‘What a brilliant phone!’ Of course, a large amount of marketing works outside the field of direct consciousness. The most effective form of persuasion is when you don’t know you’re being persuaded.

So I don’t think it’s a coincidence that Jobs and Musk – and for that matter Edison and Ford – are brilliant hucksters and showmen as well as great inventors. What’s more, I suspect that if James Dyson were less telegenic, and less talented as a storyteller, you might still have a Miele not a Dyson in your home.

If you have a Dyson rather than a Miele at home, it’s probably partly thanks to James Dyson’s talent as a storyteller (Photo: Shutterstock)

Almost all innovation requires marketing. In fact, scientific progress itself requires marketing. In its earliest stages, any behaviour, belief or technology – if it is to become widespread – must replace something else, which has typically become deeply entrenched and normalised. The early adopters of new beliefs and technologies must therefore behave in a way that looks weird to the majority of their contemporaries, risking social embarrassment or general opprobrium. (I discovered this in 1989 when I answered a mobile call on Oxford Street, using a brick-sized Motorola phone, and two people shouted abuse at me from passing cars.)

Public resistance is true of every new technology or belief in its earliest stages and has applied not just to mobile phones but also to domestic electricity, cars, trains – even (as we’re experiencing with Covid-19) vaccination. In 1796, after discovering the smallpox vaccine, Edward Jenner spent the rest of his life persuading people it was safe, fighting both religious objections and the scaremongering of quack doctors, who stood to lose money from their alternative treatments if vaccination were widely adopted.

I particularly like a 1920s Dublin ad promoting the installation of electricity in the home. Today, if you buy a remote cottage that’s not connected to mains electricity, you won’t need a lengthy sales spiel to convince you to wire up to the grid, but back in 1927 you did. We tend to forget the role that marketing plays in the early-stage adoption of new technology.

This applies equally to ideas and beliefs, from female suffrage and same-sex marriage to civil rights and the abolition of slavery. It even applies to scientific beliefs – indeed the Theory of Evolution is arguably still not a mainstream belief in the United States, 164 years after Darwin came up with it.

In 20 years or so, we’ll probably think the internal combustion was a terrible idea and it seems absurd that electric cars failed the first time around because they were deemed too feminine. Now the market is gaining traction and new players, such as British company Soventem, are set to shake up the industry (ecryptocar.com)

It is inconceivable even to imagine that there might be benefits to human slavery. But the greatest minds of past centuries, including Benjamin Franklin, took a lifetime to arrive at the conclusion we now take for granted – that it is totally unacceptable in any circumstances.

What I’m saying is that while the most effective marketing isn’t exactly invisible, once a new equilibrium or consensus has been achieved, in hindsight we forget that it required persuasion in the first place. As a present-day example, consider electric cars. Currently the subject of controversy, there is a high chance – though not a certainty – that in 2050 we’ll regard the internal combustion engine as a quaint curiosity. Interestingly, one reason why electric cars died out after some early success in the early 20th century might well have been a marketing failure – they were seen as ‘feminine’. Henry Ford and his previous employer Edison did once co-operate to build an electric car, but the project went nowhere.

Consider how attitudes to video conferencing have changed since the pandemic. Although there was no significant technological advance in video quality between 2018 and 2020, what shifted was public opinion, because lockdown forced everyone to meet virtually. The social context of video calls went from ‘weird’ to ‘normal’ and will probably stay that way, thanks to climate change campaigning against flights. Back in 2018, suggesting a video call instead of flying to New York for a two-hour meeting would have implied disrespect to your client – that you couldn’t be bothered to see them in person. Today, the idea of flying from London to New York for a couple of hours when you could simply talk by Zoom, seems outlandishly unsustainable.

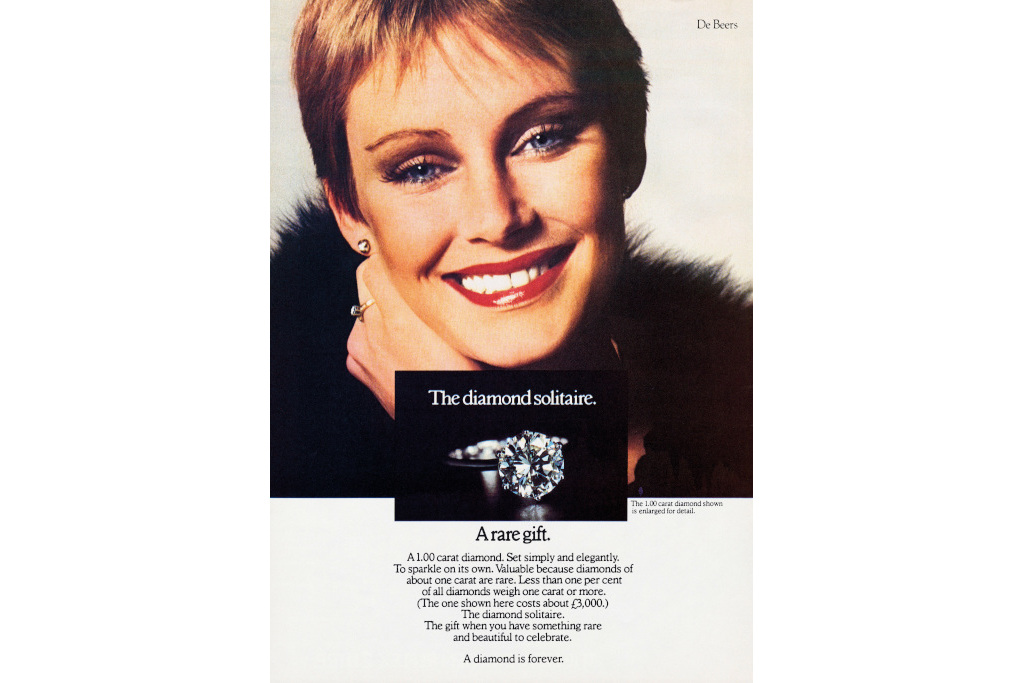

So it’s not advertising and marketing that change products per se. But they can change what the products signify. Take the current belief that a diamond is the most precious stone for use in high-end jewellery or engagement rings. In fact, diamonds are not especially rare. It was a global advertising campaign, started by de Beers in the 1940s, that convinced us of this fallacy. The campaign didn’t change what a diamond is, but transformed the perception of what it feels like to receive one as a present.

It was thanks to an advertising campaign by De Beers that we came to believe in the rarity of diamonds (Photo: Alamy)

Now, this is important, because it suggests that the techniques that made diamonds de rigueur for engagement rings can also be used, for example, to tackle climate change or wealth inequality or diversity. A great deal can be achieved through persuasion, rather than compulsion.

Government, largely populated by lawyers (who occasionally talk to economists), tends to try and tackle change the wrong way around, starting with legislation. If that fails, it moves on to economic incentives, such as bribing people. Only when those two have failed does government resort to persuasion. Smart motorways are not a wholly bad idea, for example, but government has introduced them without explaining how they work.

Advertising people know they have this power of persuasion. Indeed, over the last few years there has been an extraordinary preponderance of advertising by commercial entities, trumpeting their own pro-societal credentials, and in many cases wanting to be seen as the agents of social change.

This practice is widely debated within the advertising industry. The movement is often well intentioned, but the real question is: ‘Is it actually effective?’ And here the jury’s out: some purpose-driven campaigns have been very successful. But others have singularly failed, and even been counterproductive.

There’s nothing new about purpose-driven advertising. The famous hilltop ad for Coca-Cola, which ended the final episode of Madmen, was a kind of celebration of one-worldness and brotherly love from the Vietnam War era. But Coke is a highly unusual brand. Its immense scale, global popularity and use as an accompaniment to sociability gives its promoters licence to talk about fellow feeling and mutual kindness that most other brands can’t touch. A comparable montage for a haemorrhoid ointment might not work.

Madmen, the slick television show that documented advertising’s golden age and whose final episode ended with famous hilltop ad for CocaCola (Photo: Alamy)

There’s a wider problem, too, because if every advertisement becomes purpose-driven, the net effect feels hectoring to the audience, and people react against the message. I don’t want my margarine to lecture me about social justice. And I certainly don’t want to be morally tutored by corporations that, behind the scenes, are seeking to reduce their tax bills at every opportunity. If we start assuming businesses are advertising for self-interested reasons and interpret their ads as cynically-motivated, brands seeking to bolster their woke credentials may end up damaging the message.

Wouldn’t it be better if, instead of every brand doing a campaign to bolster its own pro-societal credentials, there were a voluntary levy on advertising, of one or two per cent, to produce messages at the category level, not the brand level, in order to promote behaviours and attitudes which could help create new, beneficial beliefs and behaviours? This would force companies to put their money where their mouthpiece is. In seeking to solve social issues, we should be careful to act in a way that’s genuinely appropriate to their solution.

Funnily enough, an organisation once existed to pursue such a purpose, from 1946 to 2011. Called the Central Office of Information, it arose as the peacetime successor to the Ministry of Information during World War II. It brought us ‘Charley says…’ (the Green Cross Code Man) and ‘AIDS: Don’t Die of Ignorance’. It also produced a slew of public information films, exhorting us not to drink-and-drive, to close farm gates, to prevent our dogs from worrying sheep, to avoid dropping litter and so forth. It was propaganda of a kind, though propaganda of a good kind, in that it simply sought to inform us what sensible social behaviour was, and to create and reinforce norms around that behaviour. Many of these ads are still working today, years after the COI has ceased its work. (Contrast your own attitude to drink-driving with that of your parents’ generation, and you might see what I mean.) Some – not all – of this shift in attitudes, from drink-drivers’ ‘regrettable acts of naughtiness’ to their current pariah status – was achieved by effective campaigns.

Be More Socially Aware banner in Piccadilly Circus

A COI-type organisation might be a better alternative to having to endure every brand on the planet lecturing us about its plans to change the world, when mostly we just want advertising to decide what kind of toothpaste we should buy.

And so my simple message here is: Yes, I think advertising might be able to save the world; but I don’t think it will do it one brand at a time.

Featured image: ‘Charley says…’, the former Central Office of Information’s campaign to help children learn road safety (Image: BFI – Crown)