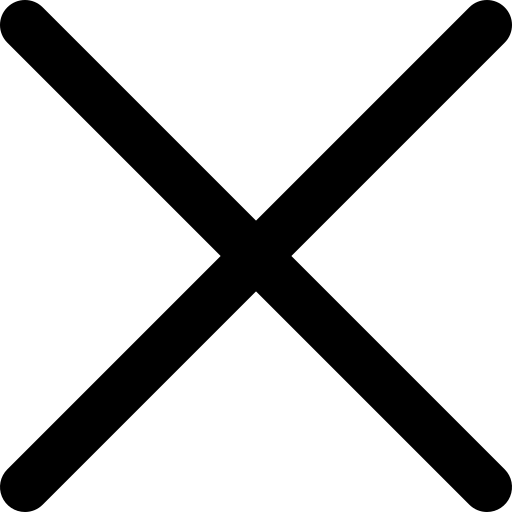

A Good Man in Literature: William Boyd

Alexander Larman meets William Boyd, the writer who has won both literary and commercial success

This post may contain affiliate links. Learn more

Ask any well-read man or woman which authors they actually enjoy reading – as opposed to dutifully keeping their books on the shelves – and the answer that often comes back is William Boyd. Author of 15 novels, several short stories, non-fiction works and film and television adaptations, Boyd’s prolific output is only matched by the excellence of its quality. It’s hard to think of a duff book written by him, which certainly cannot be said of some of his contemporaries, and his stories manage the rare hat trick of being highly readable, imbued with deep intelligence and selling in very considerable numbers. No wonder that the house where I meet Boyd is a particularly lovely example of a 19th-century Chelsea residence, where the trappings of literary success – countless books, many rare; a David Hockney collection – are on full display.

His Reputation Proceeds Him

Many writers of Boyd’s reputation exhibit a certain degree of self-awareness about their standing in the world of literature, but the friendly, open and witty man sitting opposite me doesn’t display any grandness of manner or approach. Little wonder that, when we meet, he’s just received a pile of manuscripts from hopeful writers wanting his much-prized endorsement. ‘I get sent five or six proof copies a week, asking for quotes, which I do tend to give. Not routinely, but often. I think publishers file me under: “He gives quotes, let’s wing one off to him and keep our fingers crossed”,’ he says.

Boyd’s most recent book, Love is Blind, is one of his best. Dealing with the young Scottish musician Brodie Moncur and his travels in the late 19th century through Scotland, France and Russia, among other places, it is a masterly achievement, simultaneously succeeding as a ripping yarn and a clever, metatextual commentary on itself. As he says, ‘I do believe in as compelling a narrative as possible – which has its own challenges and its own systems – but at the same time you can allude to “the grand plan” and leave clues and hope that people pick them up. I often hope that a reader will head to their reference books if there’s something they don’t quite understand, as it’s certainly something that I do. It’s a good thing to do, but it doesn’t impair the surface enjoyment factor.’

The Best Art Coffee Table Books

As usual, not all the critics quite got it. ‘I’m an old gunslinger when it comes to being reviewed, and I always get a mixed bag. Typically it’s three great ones, a lot of perfectly decent notices, and three stinkers. I’m used to it, but with Love Is Blind, which did get 80 per cent glowing reviews, it was frustrating because writers didn’t seem to get what was going on. I’ve been covered by some of the same people since 1981, and they’re almost schoolmasterly – “tut tut, pull up your socks”, and all that sort of thing. But I’m thick-skinned; I don’t curl up in a foetal position and ruin family life for the next fortnight.’

Seriously Funny

He’s well known for both his ‘serious’ and ‘funny’ novels but doesn’t see a particular division between the two. ‘I began my career as a “serious comic novelist”, because I think that my view of the world is essentially comic. When you look at the human condition, you have a choice, whether to weep or laugh, and writers I like – Chekhov, Nabokov, Muriel Spark and Waugh – all have that angle on the world. But life is a fraught and serious business, and so I find myself instinctively leaning towards dark comedy.’

House Guest: The C&TH Interiors Podcast

Although Boyd has worked in a vast number of genres and styles – including a well-received James Bond novel, Solo – the book which is probably most loved is his 2002 masterpiece, Any Human Heart, the fictionalised journal of the writer Logan Mountstuart. When asked to explain why it’s been so popular since its initial publication, Boyd replies: ‘I genuinely don’t know what book I’ll be remembered for, but I do get three times the letters about Any Human Heart as I do about my other novels. There is something about it that appeals to people; it’s probably my bestselling or at least my most consistently selling, book and there’s something about it that people respond to. It’s interesting that a lot of very young readers enjoy it; I think it’s because it’s written as a journal. Interestingly, the first letter I got about it was from a 16-year-old girl from Amsterdam, who said, “It made me think about my life to come”. It makes them think about what’s going to happen in their lives, but also to think about older people in their lives anew’.

“I’m an old gunslinger when it comes to being reviewed, and I always get a mixed bag. Typically it’s three great ones, a lot of perfectly decent notices, and three stinkers”

The Mighty Novel

He has a wide variety of projects on the go at the moment – a TV series, a play, another novel and a second volume of non-fiction, More Bamboo, but one thing that you won’t be seeing from him ‘unless I’m broke’ is either an autobiography or an authorised biography. ‘It must be very strange to read the facts of your own life: how much money you earned, who you slept with and so on. And you can end up with a proper demolition job, even in an authorised biography, as in Patrick French’s account of VS Naipaul, where one ends by thinking “what a shockingly awful man he was”. Still, as a friend of mine put it, “all biography is fiction, which has to be kept in public facts”. I won’t write a biography, nor authorise mine – but then to be fair, unless you’re Ernest Hemingway and have led a gloriously rackety life, writers’ lives are often dull.’

11 Famous Writers’ Homes You Can Visit

It’s hard to think that someone as civilised, erudite and engaging as Boyd – whose wide social circle famously included David Bowie, with whose help he published a spoof memoir of a fictitious painter, Nat Tate: An American Artist – has led a remotely dull life. Still, as he reflects, ‘I work in a wide variety of areas – films, television, literature, theatre – but it’s always the novel I come back to. It has utter freedom and flexibility, and you can do anything that you want within it’. As his legion of devoted readers knows, the way he’s taken advantage of this freedom has had the most splendid consequences – both for him and us.