- HOME

- TRAVEL

On The Road To Timbuktu: Peter Hughes On His Remarkable Life In Travel

From getting lost in the Sahara to being rescued by German smugglers, the travel writer's adventures are ones to remember

By | 2 years ago

What starts out as reckless adventure to Timbuktu ended in an accumulation of wisdom. Travel veteran Peter Hughes pays homage to the passion that sustained his career.

Peter Hughes: Trips Of A Lifetime

Since childhood I have had a compulsion to travel. I didn’t question why: with compulsions you don’t. I loved it, and that was enough, and if you’re wise you don’t question love either.

I know where it started: in Suffolk where my father farmed. The nearest village was a mile away which, when you are six, amounts to short haul. My first travels were strictly domestic.

Past the farmhouse, and the barn and cattle yard, was an ancient shed. Timber-framed, with rough clapboard walls and a roof of wrinkled pantiles, it marked the edge of the homestead. Beyond lay Badlands and adventure. With any luck both. A cart track wound through thickets of bramble and hazel into a forbidding wood called Mellfield. It was the first part of the world I explored on my own.

For me, travel was a quest for adventure, at times almost reckless. But while there may be no wisdom in choosing to travel, one is invariable wiser for having travelled. At the age of 17 I went to America on a whim; ten years later to Timbuktu on a prayer. Since then I have shown my passport at the borders of more than 140 countries. Those early journeys led to my crossing Siberia by train, entering Captain Scott’s hut in the Antarctic, flying in the cockpit of Concorde, transiting the North West Passage, tracking tigers in India from the back of an elephant and steaming to the Ganges Delta on an ancient paddle-wheeler called the Rocket in Bangladesh.

Peter Hughes in Antarctica

My time in America came about because I was bored at my English boarding school. At a morning assembly early in 1960, the headmaster made a perfunctory announcement about there being no candidates for that year’s English-Speaking Union student exchange scholarship. It would be a pity, he reflected, if no one applied. Ten minutes later, on my way to the first lesson of the day, I decided to do so. It was an impulse that resulted in my spending a year in the United States. At the time I had never been further than Wales.

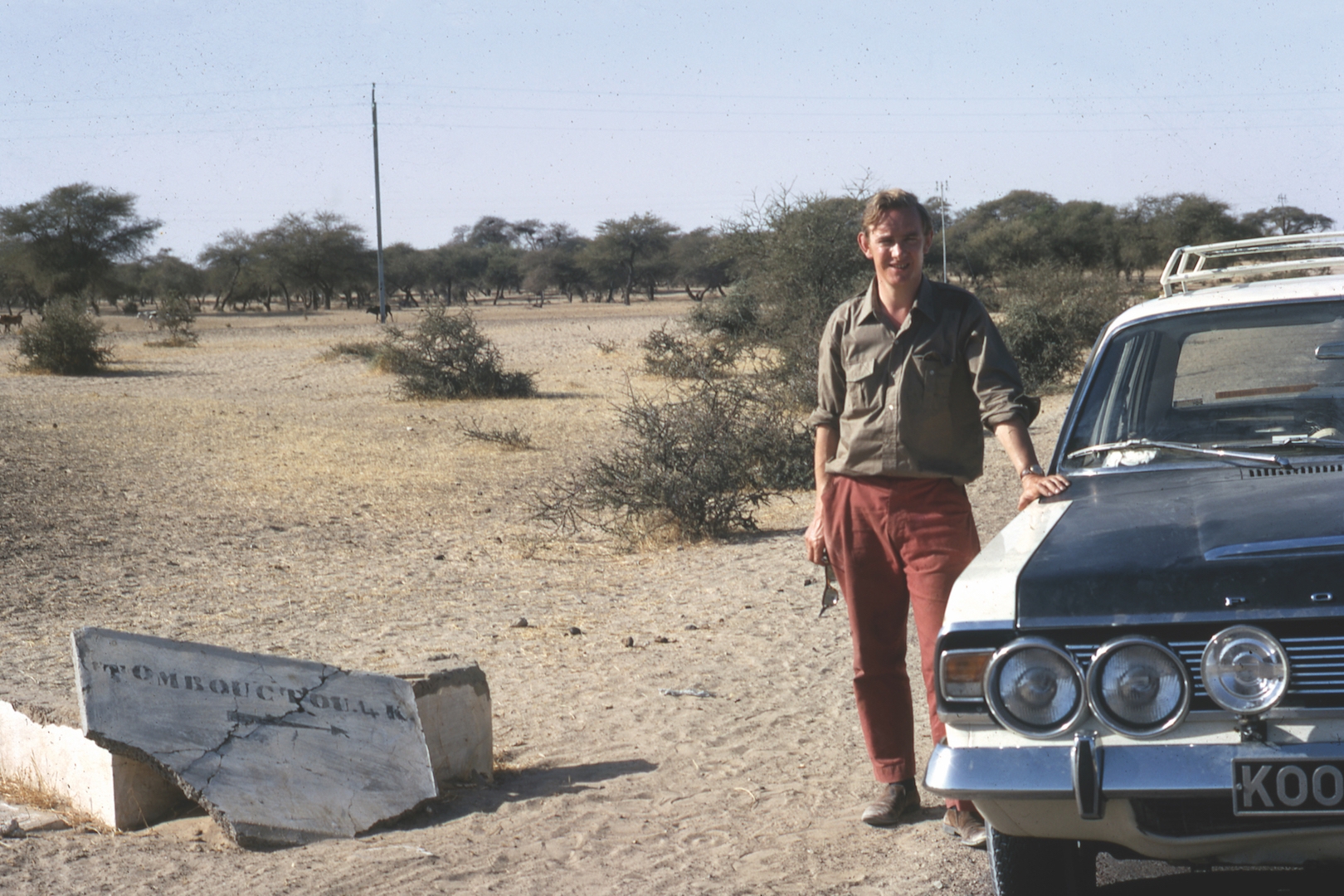

Tumbuktu

The journey to Timbuktu was more considered, though now it sounds more like ‘a-good-idea-at-the-time’. The plan was to drive from London to Timbuktu and back in a fortnight – the typical duration of a family holiday. What made the idea so good was that I would do it in a Range Rover which had just been launched. I and a companion would take the most exciting car of its time to legendarily the remotest place on earth. Here was a vehicle that could take the children to school in the week, cruise to the coast at weekends and nip across to Africa for a winter break in Mali.

What made it not such a good idea was that Range Rover wanted no part of it. Never mind, my companion, the late Eric Jackson, was a Ford works rally driver. Ford were about to replace a model called the Zephyr and had lots unsold. How many would we like? Whatever the Zephyr’s virtues on the highway, few cars were less suited to the Sahara Desert.

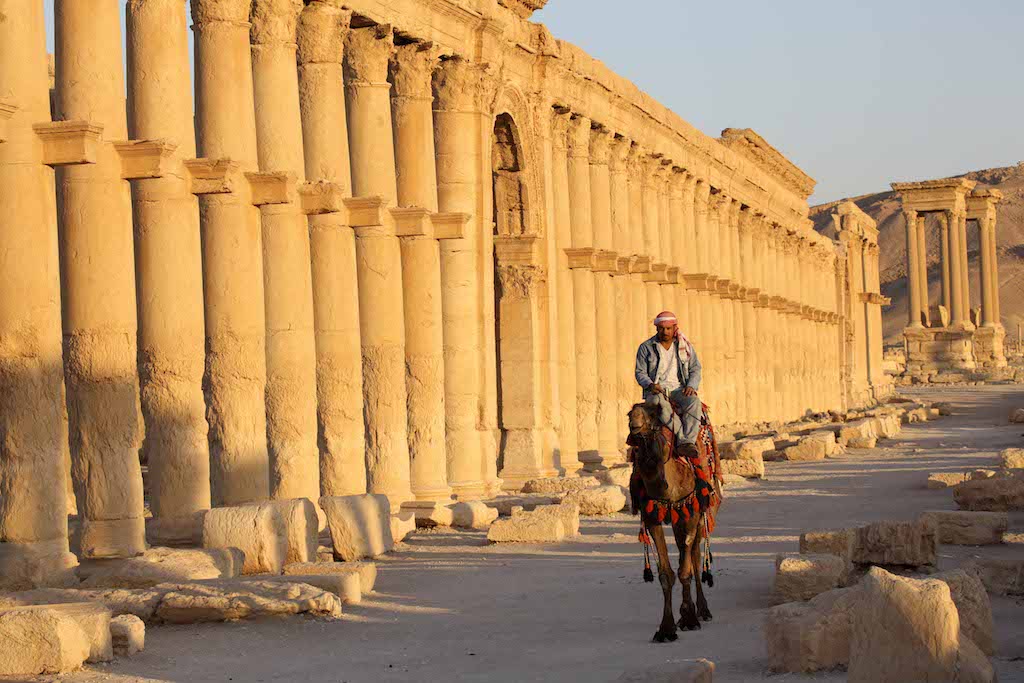

The Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus

Inevitably the expedition came to grief. With 200 miles to go to the fabled city, the car was expiring. Too late we realised that the Zephyr’s engine had been guzzling Saharan sand in much the same way as a baleen whale ingests krill. We reached Timbuktu only by loading the car on to a dilapidated ferry and steaming for two days on the river Niger. Our boat, the Liberté, built in France in 1928, had no engine but was towed by a fuming tug with a corrugated tin roof and half a dozen goats in the stern.

Timbuktu was made from mud. It looked more the result of erosion than construction. Streets ran in sand-filled gulleys between houses the colour of fudge; a small fruit market was spread in the shade of a large acacia tree, and women drew their headscarves across their faces at the sight of foreigners. It hardly lived up to its mystique.

The most imposing buildings were three medieval mosques, remnants of Timbuktu’s eminence as one of the most important universities of the Islamic world. The mosques were also built of mud, their minarets, thickset, tapering towers, prickly with protruding wooden poles used as ladders.

The sand in the streets was ankle deep, enough for the car to get stuck. We paid a jeep driver to push us free. After just two hours we loaded back on to the Liberté and began the journey home. It was another 500 miles before the car died, almost astride the Tropic of Cancer in the centre of the Sahara. We were 250 miles from any habitation and still nearly 4,000 miles from London. After three days we were rescued by a band of German smugglers. They were heading south to buy contraband gold in Ghana. Our two-week jaunt had taken a month and the Zephyr was abandoned to the desert.

My trips to Timbuktu and America founded my contention that when you travel is as important as where. In Timbuktu I was lucky to get there before a Jihadist rebellion put most of Mali out of bounds. In America I witnessed both renaissance in the election of President Kennedy and abomination of a South still racially segregated. I give thanks for having seen Syria before the atrocities of the civil war.

Peter managed to visit Syria before the civil war

Prague

In Prague too my timing was right. Though nothing is more sterile than being told you should have been here yesterday, I first went in 1969, the year after the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia to demolish any incipient twitch of democracy. But then everyone who goes anywhere sees it for the first time. Prague was monochrome and oppressive. Russian tanks were still on the streets; visitors were frequently followed, and their rooms bugged. My hotel was unaccountably changed as soon as I arrived. Typical.

Twenty years later I was back, just weeks after the Velvet Revolution had seen the overthrow of communism. Hoardings erected in Wenceslas Square displayed reports of the most important events of the previous 40 years, news the Czechs had been denied. Although Prague was en fête, its fabric was pristine. Streets of untouched and stunningly beautiful buildings were hardly changed since Mozart lived there. I saw no plate glass shop windows and virtually no neon. It was also astoundingly cheap. A seat at the opera cost £3.

And now what? Local cultures, communities, and endangered wildlife, have long harvested the benefits of tourism. They have suffered gravely from the Covid pandemic and tourism’s collapse. In the plague’s uncharted aftermath, travel will have to be questioned and justified like everything else in the ‘new normality’. My hope is that among the other ‘proceeds’ from travel, we might count international rapport. Where politics creates stereotypes, tourism dismantles them.

During my first visit to Damascus a car bomb in the city killed a leader of Hezbollah. The following day I went to the Great Umayyad Mosque. The imam was delivering his sermon at Friday prayers. I asked my interpreter what he was saying. ‘He is speaking about yesterday,’ he said. ‘What, exactly,’ I asked warily. ‘Yesterday was St Valentine’s Day and he is talking about the importance of love.’

MORE TRAVEL FROM PETER:

A Whale Of A Time: Peter Hughes Discovers Indonesia / Plane-Free Luxury Travel: 5 of the Best

First published in Country & Town House in print in July 2020